Serving under Charles I, Oliver Cromwell and Charles II during his time at The Royal Mint, Thomas Simon is one of the finest engravers that Britain, indeed the world, has ever known.

Producing intricate works on the small canvas of a coin, particularly during an era before powerful coining presses or advanced minting technology, Simon possessed superlative engraving skills and artistic talent; his work was even acknowledged in the diaries of Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn. Simon’s Petition Crown, crafted by hand in 1663, is the coin for which many know him best.

The Son of a Merchant

A book written by George Vertue in 1753 heavily influenced many accounts of Thomas Simon’s life. In the work, which was published as an enlarged, second edition in 1780, Vertue claimed that Simon was born in 1623, when in fact he was probably born in 1618, the fourth son of Peter and Anne. Records of the Huguenot Society of London show that his parents married at the French Church in Threadneedle Street in the City of London on 12 September 1611. His father was a London merchant of either French or Guernsey descent and his mother was from Guernsey.

Learning his Craft

Records from the Goldsmiths’ Company show that Simon was initially an apprentice to George Crompton for eight years from 29 September 1633. However, after two years, Simon found the arrangement unsatisfactory and changed his master, apprenticing to Edward Greene who was Chief Engraver at The Royal Mint. Whilst learning his craft under Greene, a Frenchman called Nicholas Briot also worked at The Royal Mint. Briot worked with Greene on matters of artistic interpretation, creating some well-executed coins in the 1630s – designs which would have been seen by Simon.

One of Simon’s earliest pieces was the Scottish Rebellion Medal of 1639, which commemorates the Treaty of Berwick. His apprenticeship under Greene ended in 1642, by which time parliament had taken over the Tower Mint following the outbreak of the Civil War. Simon had chance to demonstrate both his engraving skill and loyalty to the Parliamentarians when Sir Edward Littleton, the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, sent the Seal to Charles I in York. Parliament needed the Great Seal to legitimise its actions and therefore asked Simon to produce a copy, which he did in 1643, committing high treason in the eyes of the Royalists.

Edward Greene died in 1644 and on 4 April 1645, Simon was appointed Joint Chief Engraver alongside Edward Wade. They shared a salary, but it is assumed that due to the unimpressive quality of the coinage during the latter half of the 1640s, Wade worked on coins whilst Simon focussed on medals.

Serving a New Regime

Simon’s engraving talents piqued the attention of Oliver Cromwell, then Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, and his Puritan leanings further endeared him to the Protector. Simon was commissioned to produce a portrait of Cromwell following the Battle of Dunbar, in which the Republican Army defeated Charles I’s supporters in Scotland. Known as the ‘Dunbar Medal’, Cromwell was extremely pleased with his portrait and appointed Simon as his personal medallist in 1651, remarking ‘the man is ingenious and worthy of encouragement’. The same year, Simon engraved the Great Seal of England, and was also ordered to engrave the Great Seal, Privy Seal, and Seal Manual. Under Cromwell, Simon also produced seals for the colonies, including Jamaica, Virginia, Barbados, Bermuda, and Ireland, county seals, many personal seals, a seal for the Order of the Garter, and a seal for the Royal Society. By 1655 he was ‘sole chief engraver for the Mint and Seals’ and, following Cromwell’s death in 1658, he was asked to produce the ‘death mask’ for the Protector’s funeral procession, which became the predominant model for subsequent busts and sculptures of Cromwell.

With Cromwell’s death came the end of any coins bearing his portrait. Simon’s designs for the coinages didn’t go unrecognised with Stephen M. Leake, an eighteenth-century numismatist, praising the coin ‘done by the masterly hand of Symonds, exceeding anything of that kind, that had been done since the Romans’.

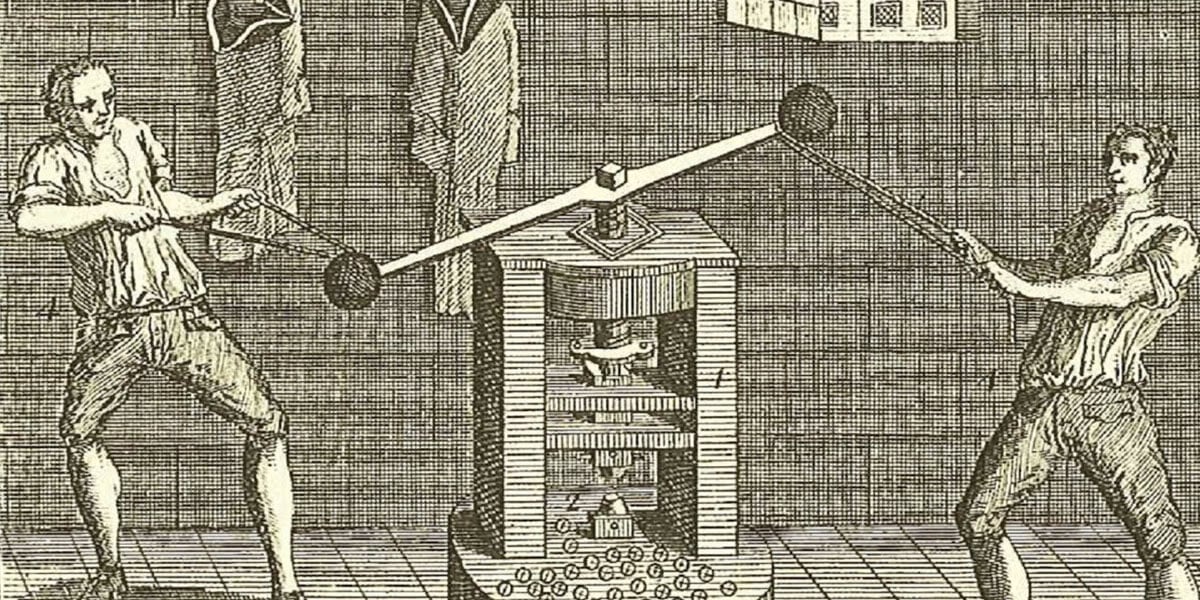

Bridging Ingenuity with Innovation

Working with Pierre Blondeau, an engineer of the Parisian Mint, Simon engraved the dies for Cromwell’s coinages in 1656 and 1658. It is claimed that during this period of work, Simon introduced a stippling to the design, which gave a frosted appearance and was the first of its kind. Simon’s working relationship with Blondeau would continue as in 1662, after the Restoration, Charles II ordered him to travel to Paris and bring the engineer back to London so he could prepare the machinery intended to produce the new coinage. The minting technology had long been in use in continental Europe, which meant that Simon played a role in helping to establish the practice in London.

Petitioning the King

In the wake of the Restoration and Charles II’s return from exile, Simon petitioned the king ‘for the employment of Chief Engraver to His Majesty and the Mint, which he held under the late King, and for Pardon, because by order of Parliament made their Great Seal in 1643, and was their Chief Engraver of the Mint and Seals’. The request was initially unsuccessful as Thomas Rawlings, who had been granted the title of Chief Engraver under Charles I, was reinstated. However, Simon continued to do most of the work typically attributed to the Chief Engraver, producing the Great Seals for Charles II.

Simon was eventually reinstated as Chief Engraver in 1661 but was further aggrieved in the form of the Roettier brothers, whose family had helped Charles II with loans during his exile in Holland. As a reward, the king invited the brothers to London to produce a new coinage . In January 1662, Simon and the Roettiers were ordered to engrave the dies for the new coinage, but resentment and ‘by reason of a contest in art between them’ rendered the working relationship a stalemate. A trial of skill ensued, whereby both sets of engravers were asked to produce a trial piece of a silver crown. The king favoured the work of the Dutchmen, which prompted Simon to produce a piece in response: the Petition Crown. The piece was so named due to the inscription, which Simon engraved by hand, and is regarded an incredible feat of engraving skill to this very day:

‘THOMAS SIMON MOST HVMBLY PRAYS YOVR MAJESTY TO COMPARE THIS HIS TRYALL PIECE WITH THE DVTCH AND IF MORE TRVLY DRAWN & EMBOSS’D MORE GRACE: FVLLY ORDER’D AND MORE ACCVRATELY ENGRAVEN TO RELEIVE HIM’

The petition was unsuccessful, yet the crown is considered as Simon’s most famous work and is widely regarded as one of the finest in numismatic history.

Death and Legacy

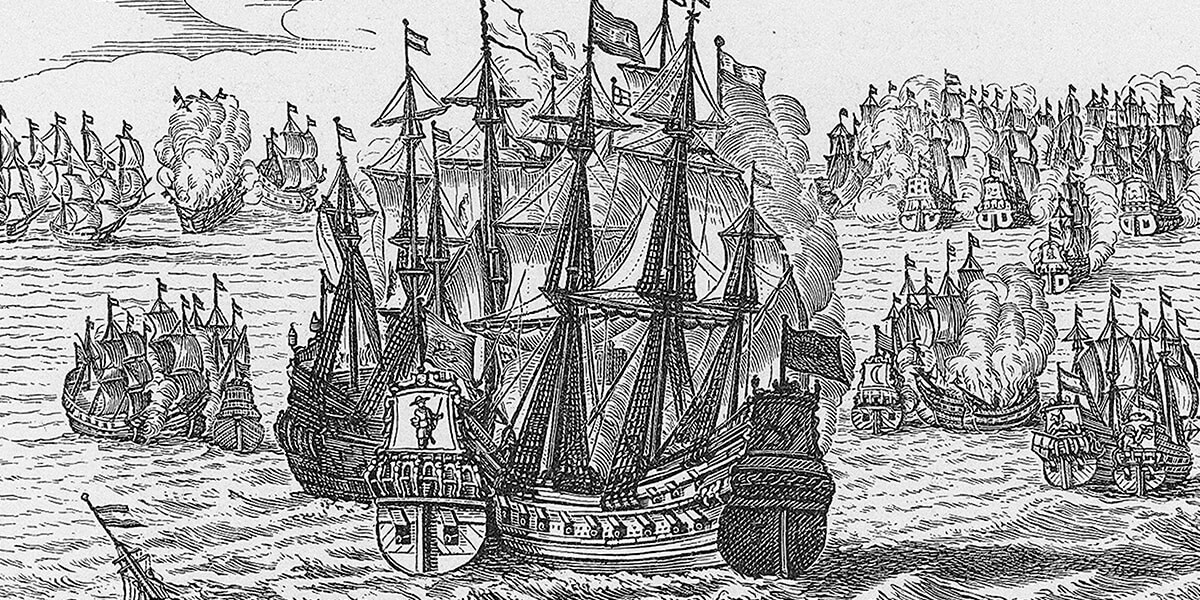

Simon continued to work at The Royal Mint and his last known work was a small yet beautifully crafted medal that commemorated the English naval victory over the Dutch in 1665. The same year, Simon died from the Plague that had struck London. Despite his passing, Simon set an incredibly high standard for the engraving profession, and 150 years would pass before his talent was matched through the works of the Wyon family and Benedetto Pistrucci.