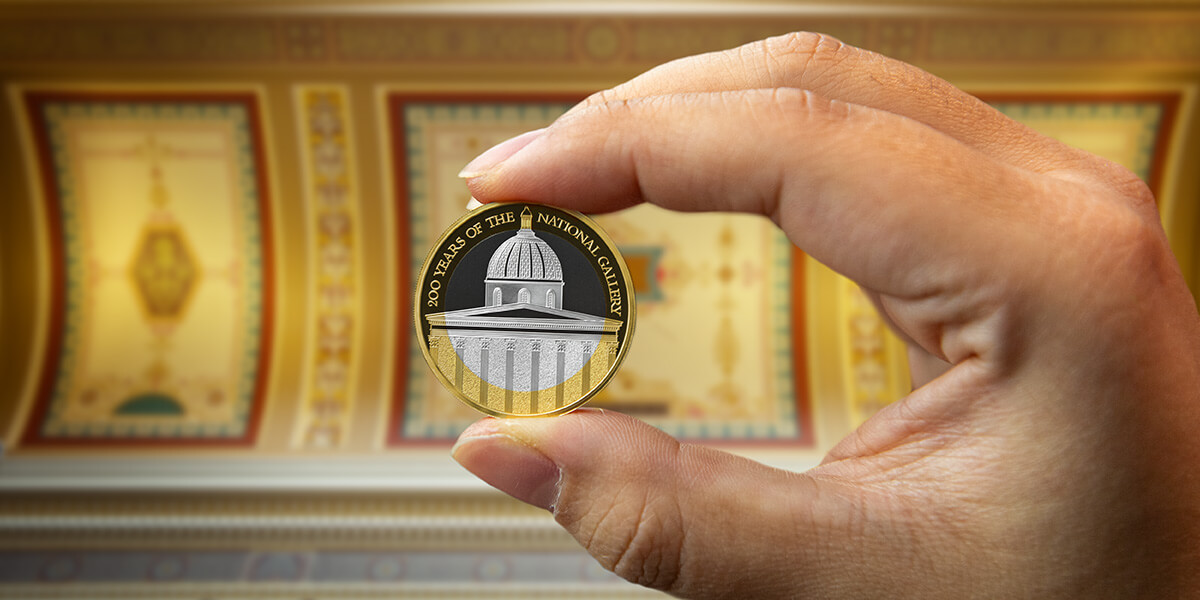

Join us as we delve into the artistic process of a pioneer of print whose impact reaches far beyond conventional artistic mediums. Celebrating 200 years of the National Gallery, Edwina Ellis’ creative influence takes centre stage in the distinctive tribute she has created for this UK £2 coin.

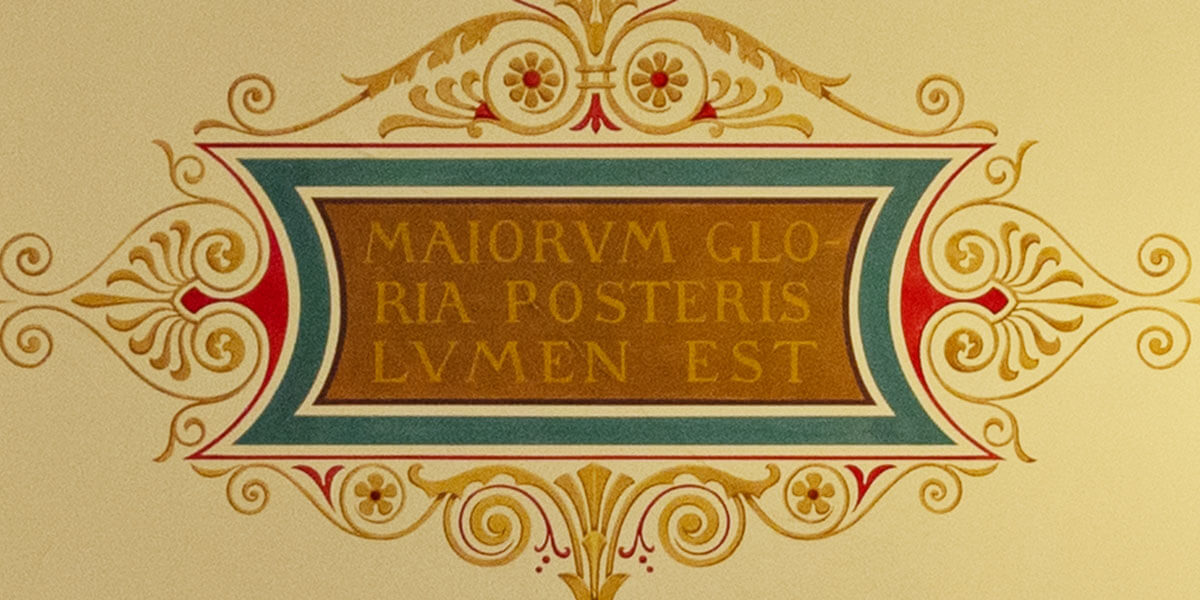

Adorned with the edge inscription taken from the ceiling of the Wilkins Building, ‘MAIORVM GLORIA POSTERIS LVMEN EST’, which translates to ‘The glory of our ancestors is a light to our descendants’ and features on certain editions of the coin, this symbolic coin bridges the past with the future and encapsulates the enduring belief that the brilliance of past artists serves as inspiration for future generations.

Born in Sydney, Australia in 1946, Edwina Ellis’ creative journey has spanned continents. In 1972, following her graduation from the National Art School where she trained as a jewellery designer, the allure of London drew her in and she went on to establish a career there.

A true innovator who has made significant contributions to the field of engraving, she has paved the way for the use of homopolymer resins and the creation of relief printing apparatus using laser-cutting techniques.

During her Fine Art Practical PhD research at Aberystwyth University, she began to delve into the world of engraving via vinyl cutting. Her impressive portfolio includes engraving polymer blocks for The Times masthead along with the creation of an ‘Art on the Underground’ poster for Transport for London that showcases London architecture through nine three-block colour engravings.

Over the past few years, the printmaker has demonstrated her artistic talents in numismatics. Her coin designs include the Bridge series created for the round UK £1 coin, which were crafted using traditional linocut techniques, and designs for the 2015 London Underground UK £2 Coin and Stephen Hawking 2019 UK 50p Coin, both of which were composed digitally.

Her remarkable blend of traditional and modern techniques showcases her diverse and exceptional artistic abilities. In this article, we catch up with the printmaker to discuss her design for the reverse of The National Gallery 2024 UK Coin.

How did you approach the challenge of creating a coin that represents such a significant institution?

“It was a bit daunting: I began by looking for original ideas to combine with recognisable elements. Significant emblems are already there, as the National Gallery has a descriptive logo and specifically adapted Roman lettering.”

Can you walk us through your creative process when starting a new coin design?

“My initial search is for abstract ideas that may translate into something graphic to combine with illustrative things like buildings or their details. Whenever possible, I go to an actual site to draw, photograph and think. One pleasurable aspect of coin design is that I am often starting with something I have never researched before. I trawl through book references and look at every angle of the subject, from its history to its actual fabric, filling my phone with photographs and jotting down a mess of facts, quotes and wonky thumbnail sketches.

“I discovered that the National Gallery was originally derided for its insignificance and wasn’t dominating a high point of Trafalgar Square as the square was sloped. It was levelled to accommodate the Jellicoe pools at the base of Nelson’s column, which made a steep cutting into the north end that seemingly raised the National Gallery.”

You have used lino and digital design tools in the past to bring coin designs to life. What medium have you chosen this time?

“I did all the design work digitally, where I can shuffle layers of text and graphics in the way that I could cut and collage linocuts together, but digital drawing has the added advantage of scaling. I often draw large, careful letters, then move, distort and scale them according to the needs of a particular design, whilst keeping the original file for the next ideas. So much of design is in juxtaposition and arrangement, especially working with such a familiar building.”

What techniques did you use to create the intricate details on the coin? How do you balance artistic expression with practical considerations such as scale?

“I always draw every graphic aspect of the subject carefully, even if supplied with drawings: I have the patience of a wood engraver. So, the gridded stonework of the windows and the dome scales are all line-drawn on my iPad. Even if a detail ends up as a blurry line, or rubbed out, you have to understand it.

“With the eventual space so tiny, simplification is constant: how much can I imply? The answer is often in rescaling and foreshortening. In this case I separated the dome from the pediment of the National Gallery, resizing and re-joining them at a point where they sat nicely in the circle.”

What was the most challenging aspect of designing the National Gallery coin?

“Nothing equals looking and photographing for yourself to uncover some aspect that is your own slant. I particularly wanted to examine the building from every angle, so I jumped on a tube to Charing Cross to take photographs before returning home to the drawing-board. The chosen design is a lot more straightforward than a lot of my ideas. I did not initially place the building front-on and central and it was quite a challenge getting it to such a small scale.”

Are there any particular design elements that you are especially proud of?

“I like the empty space each side of the bottom edge of the pediment; it is an important part of the design – so-called empty space often is. I have always loved the leaden scaly dome atop the National Gallery, so it was a pleasure to feature it. I didn’t mind having to render each scale, but I think a roofer might have leaded the actual dome faster.

“Bimetal is always a fun consideration. Should I use it as a border for the text? Maybe I should cut the dome lantern on its join, or perhaps I should ignore it and send a row of Greek columns straight through it.”

Can you share any particularly memorable moments or experiences you’ve had while designing numismatics?

“Seeing my design realised in a tiny bar relief with a shiny background is a bit like pulling the first proof of a print that I’ve worked on for weeks. Although familiar with every aspect of the design, the paradox of recognition coupled with surprise – always surprises.

“I love how coinage has affected our language, like ‘ringing true’, so when I was working on the Bridge £1 coin designs, the Chief Engraver said ‘on the other side of the coin’, I waited for his opposing argument, before realising he meant the monarch’s portrait. For a lone-working artist, it’s always a huge pleasure to have designs going through to the minting process: a change to be part of a team. The designers and engravers at The Royal Mint encourage, consult, tidy up and frankly improve my designs while realising them in bar relief, cutting dies for them.”